Use of Seasonal Influenza and Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccines in Older Adults to Reduce COVID-19 mortality

This study has not yet been peer reviewed.

(1) International Vaccine Access Center, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA.

(2) Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, South Africa.

Background and Aim

SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19 has emerged as a pandemic with all continents now reporting cases, most of them community acquired [1]. Many COVID-19 infections cause pneumonia and some are fatal, predominantly among older adults [2]. Co-infection with other viruses or bacteria, particularly those that similarly cause inflammation of the respiratory tract would likely enhance the risk for severe COVID-19 disease. Such disease enhancing co-infections have been frequently reported for respiratory pathogens [3–5], most notably so for the 1918 influenza pandemic [6,7]. Vaccinating older adults at elevated risk of severe COVID-19 disease against vaccine preventable diseases may therefore not only help to reduce the strain on the healthcare system from those diseases during a pandemic, but also alleviate some of the potential COVID-19 mortality due to co-infecting pathogens [8].

Vaccines that can prevent respiratory tract infections in adults and particularly in older adults, either through direct protection or indirectly through high coverage childhood immunisation programmes, include vaccines against seasonal influenza, Streptococcus pneumoniae, measles, Bordetella pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib). Measles, pertussis and Hib vaccines are already included in almost all routine infant immunisation programmes globally and have largely eliminated the targeted pathogens as a risk to the older adult population through indirect protection [9]. Hence, they have limited scope for use in older adults in order to limit COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), either 10- or 13-valent, is used in three-quarters of routine infant immunisation programs globally; in countries that use PCV, the burden of adult pneumococcal disease due to PCV serotypes has also substantially decreased [10]. These considerations mean there is a relatively small preventable disease burden in countries routinely using PCV in children. As vaccine costs are relatively high and there is no current World Health Organisation recommendation regarding PCV use in adults, PCVs are not considered further here. Two vaccines that target a large burden of the remaining respiratory disease in older adults are seasonal influenza vaccines and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23). These vaccines are only included in routine adult immunisation in some countries and even there with only moderate coverage [11]. We aim to evaluate whether vaccination of older adults with seasonal influenza vaccine or PPV23 could help reduce COVID-19 mortality.

Seasonal Influenza Vaccines

The World Health Organization recommends seasonal influenza vaccine use for pregnant women as well as older adults (>65yrs), health care workers and persons with specific chronic illnesses (particularly HIV) [12]. In 2014, 45% of countries globally had established a seasonal influenza vaccine programme that targets older adults, hardly any of them are in low or middle income countries [13].

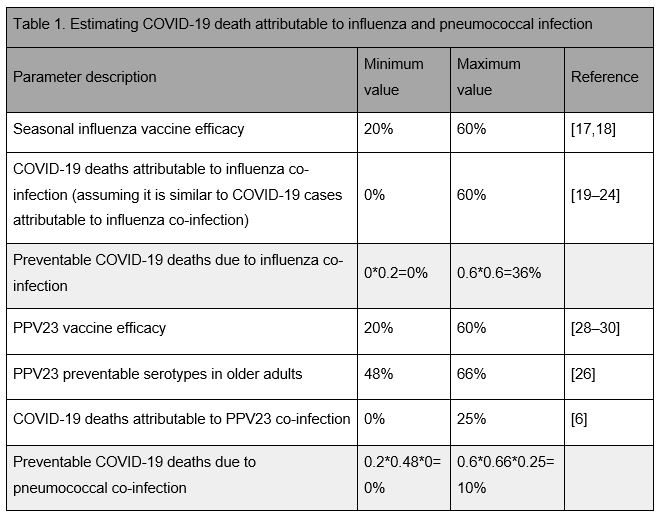

Seasonal influenza as a risk factor for COVID-19 could be an important consideration in tropical climates and the southern hemisphere, and potentially during future waves of COVID-19 in the northern hemisphere [14–16]. Inactivated influenza vaccine effectiveness varies markedly by season from about 20% in seasons with a poor match to the circulating strains to up to 60% for closer matched seasons [17,18]. Hence, influenza vaccination could prevent 20% to 60% of influenza infections and thereby potentially a similar percentage of influenza-attributable COVID-19 morbidity and mortality (Table 1).

A number of studies to date have tried to assess the percentage of influenza-attributable COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. Some reported the occurrence of co-infection of COVID-19 inpatients with influenza viruses, although the proportion of co-infections varies by study, from no influenza coinfection identified to more than 60% of PCR positive COVID-19 patients being currently or having been recently infected with influenza [19–25]. Whether this co-occurrence is co-incidental or indeed influenza contributes to the clinical severity of COVID-19 presentation is not yet clear. However, to date there is no evidence that would suggest clinical manifestations in COVID-19 patients with influenza co-infection differ from those without co-infection [19].

Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine

PPV23 targets 23 of the over 90 serotypes that are responsible for most adult pneumococcal disease. In countries with an infant PCV program, about 48-66% of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in older adults is caused by serotypes that PPV23 is effective against [26]; in countries without an infant PCV programme this percentage is likely about 20% higher (details see Appendix). PPV23 is recommended for routine use in older adults in most high-income countries, but rarely in low and middle-income countries [27]. It provides short-term protection against IPD caused by vaccine serotypes in healthy older adults with a pooled efficacy across targeted serotypes of about 60% [28–30]. However, PPV23’s effectiveness is much lower among high risk groups including the immunocompromised [31–33], who may be at particular risk for severe COVID-19. Consequently, PPV23 use in older adults could prevent up to 33-40% of pneumococcal disease and thereby potentially pneumococcal-attributable COVID-19 morbidity and mortality (Table 1).

The extent of pneumococcal-attributable COVID-19 morbidity and mortality is largely unknown. Pneumococci have been identified as a major source for often fatal secondary bacterial infections during pandemic and seasonal influenza infections. Estimates for the proportion of pneumococcal co-infections among pandemic influenza deaths range from about 7% during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic to more than 50% during the 1918 pandemic [6,34–37]. Few studies so far have tried to identify bacterial co-infections among COVID-19 cases, and those that did found very few bacteria and only a limited number of cases with pneumococci [23,38,39]. This may be due to the empirical treatment with antimicrobials for the majority of severely ill suspected COVID-19 patients, or because bacterial infection plays little role in the severity of COVID-19 disease [23,40]. However, elevated procalcitonin levels, a sensitive but not very specific biomarker for bacterial infections, have been reported in 13% of severe and 25% of fatal COVID-19 infections, but largely absent in COVID-19 infected persons with less severe outcomes, which may suggest some role for bacterial coinfection [41,42].

COVID-19 Associated Risks of Attending Clinics to Receive Influenza or PPSV23 Vaccination

Attending a vaccination clinic during the COVID-19 pandemic will likely come with an excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. This risk may be small, particularly if physical contact reducing interventions are implemented. To illustrate the potential magnitude of such excess risk, we assume a reasonably high COVID-19 burden scenario: contact reducing interventions can be implemented and upheld to substantially slow COVID-19 spread but not contain it, so that after 6 month and in the absence of a COVID-19 vaccine herd immunity will end the outbreak [43]. Assuming a basic secondary attack rate of R0=2.5 and that contact-reducing interventions spread the COVID-19 infection risk equally across that 6-month time period, the increase in risk for COVID-19 acquisition attributable to the vaccination clinic visit would be roughly 0.3-1.4%, depending on the effectiveness of transmission-reducing measures during the vaccination visits (details see Appendix) [44]. This implies, that if either seasonal influenza vaccine or PPV23 reduces COVID-19 morbidity and mortality by a similar amount or more, their benefit on COVID-19 alone would outweigh the risk associated with the vaccination visit in this scenario.

Conclusion

Both seasonal influenza vaccine and PPV23 can prevent a substantial burden of targeted disease and mortality among older adults and adults at-risk. Despite a potential collateral reduction in influenza and pneumococcal circulation due to contact reducing interventions, in countries where the COVID-19 pandemic coincides with the season of high risk for pneumococcal and/or influenza disease, vaccination at high coverage will have added benefits: minimising the number of pneumococcal and influenza hospital admission reduces the resources needed to care non-COVID-19 patients and minimises the risk of health-care acquired COVID-19 infection. For influenza, the similarity of symptoms with COVID-19 cases also suggests that vaccination will increase the specificity of syndromic COVID-19 surveillance and interventions.

The magnitude of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality prevented by influenza vaccine and PPV23 is probably relatively small, although at present we cannot exclude the possibility of either preventing a considerable amount of COVID-19 related mortality (Table 1). This uncertainty highlights the importance for detailed monitoring and additional studies where possible, in both high and low income settings. The proportion of vaccine preventable COVID-19 morbidity and mortality could be assessed, for example, by post mortem examinations or test-negative case-control studies [45].

In summary, where already in routine use with high uptake among older adults and/or adults at-risk, both seasonal influenza and PPV23 have the potential to not only reduce the burden of the targeted diseases but also prevent a proportion of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, if they can be delivered while minimising the risk for SARS-CoV-2 transmission. However, for countries without routine use, there is currently little evidence to encourage implementation of either seasonal influenza vaccine or PPV23 programmes for older adults solely for the purpose of reducing COVID-19 mortality.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Adam L. Cohen, Shalini Desai, Raymond Hutubessy and Ann Lindstrand of the World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, for insightful discussions at all stages of this work. We would like to thank all of the PSERENADE Team site investigators who contributed IPD surveillance data to the global serotype distribution analysis. The PSERENADE project is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the World Health Organization.

References

[1] Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Geneva, Switzerland: 2020.

[2] Verity R, Okell LC, Dorigatti I, Winskill P, Whittaker C, Imai N, et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;0. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7.

[3] Madhi SA, Klugman KP, Vaccine Trialist Group. A role for Streptococcus pneumoniae in virus-associated pneumonia. Nat Med 2004;10:811–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1077.

[4] Hers JF, Masurel N, Mulder J. Bacteriology and histopathology of the respiratory tract and lungs in fatal Asian influenza. Lancet Lond Engl 1958;2:1141–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(58)92404-8.

[5] Bosch AATM, Biesbroek G, Trzcinski K, Sanders EAM, Bogaert D. Viral and bacterial interactions in the upper respiratory tract. PLoS Pathog 2013;9:e1003057. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003057.

[6] MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AA, Barnes M, Ridda I, Seale H, Toms R, et al. The role of pneumonia and secondary bacterial infection in fatal and serious outcomes of pandemic influenza a(H1N1)pdm09. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:637. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3548-0.

[7] Brundage JF. Interactions between influenza and bacterial respiratory pathogens: implications for pandemic preparedness. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:303–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70466-2.

[8] WHO. Immunization in the context of COVID-19 pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2020.

[9] Wahl B, O’Brien KL, Greenbaum A, Majumder A, Liu L, Chu Y, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6:e744–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X.

[10] World Health Organisation. WHO | Data, statistics and graphics | Vaccine Introduction slides. WHO n.d. http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/ (accessed April 13, 2020).

[11] Mendelson M. Could enhanced influenza and pneumococcal vaccination programs help limit the potential damage from SARS-CoV-2 to fragile health systems of southern hemisphere countries this winter? Int J Infect Dis 2020:S1201971220301491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.030.

[12] Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Releve Epidemiol Hebd 2012;87:461–76.

[13] Ortiz JR, Perut M, Dumolard L, Wijesinghe PR, Jorgensen P, Ropero AM, et al. A global review of national influenza immunization policies: Analysis of the 2014 WHO/UNICEF Joint Reporting Form on immunization. Vaccine 2016;34:5400–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.07.045.

[14] Cohen AL, McMorrow M, Walaza S, Cohen C, Tempia S, Alexander-Scott M, et al. Potential Impact of Co-Infections and Co-Morbidities Prevalent in Africa on Influenza Severity and Frequency: A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE 2015;10:e0128580. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128580.

[15] Wong CM, Yang L, Chan KP, Leung GM, Chan KH, Guan Y, et al. Influenza-Associated Hospitalization in a Subtropical City. PLOS Med 2006;3:e121. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030121.

[16] Viboud C, Alonso WJ, Simonsen L. Influenza in Tropical Regions. PLOS Med 2006;3:e89. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030089.

[17] Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X.

[18] CDC. CDC Seasonal Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Studies | CDC 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/effectiveness-studies.htm (accessed April 13, 2020).

[19] Ding Q, Lu P, Fan Y, Xia Y, Liu M. The clinical characteristics of pneumonia patients coinfected with 2019 novel coronavirus and influenza virus in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 2020;n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25781.

[20] Xing Q, Li G, Xing Y, Chen T, Li W, Ni W, et al. Precautions are Needed for COVID-19 Patients with Coinfection of Common Respiratory Pathogens. MedRxiv 2020:2020.02.29.20027698. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.29.20027698.

[21] Wu X, Cai Y, Huang X, Yu X, Zhao L, Wang F, et al. Early Release - Co-infection with SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza A Virus in Patient with Pneumonia, China - Volume 26, Number 6—June 2020 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC n.d. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2606.200299.

[22] Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID-19 infection: Different points from adults. Pediatr Pulmonol 2020;n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.24718.

[23] Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. The Lancet 2020;395:507–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7.

[24] Shah N. Higher co-infection rates in COVID19. Medium 2020. https://medium.com/@nigam/higher-co-infection-rates-in-covid19-b24965088333 (accessed April 6, 2020).

[25] Kim D, Quinn J, Pinsky B, Shah NH, Brown I. Rates of Co-infection Between SARS-CoV-2 and Other Respiratory Pathogens. JAMA 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6266.

[26] PSERENADE, von Gottberg A. Pneumococcal Serotype Replacement and Distribution Estimation (PSERENADE) Project. PSERENADE Serotype Distrib COVID-19 Model 2020.

[27] Bonnave C, Mertens D, Peetermans W, Cobbaert K, Ghesquiere B, Deschodt M, et al. Adult vaccination for pneumococcal disease: a comparison of the national guidelines in Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2019;38:785–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-019-03485-3.

[28] Andrews NJ, Waight PA, George RC, Slack MPE, Miller E. Impact and effectiveness of 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease in the elderly in England and Wales. Vaccine 2012;30:6802–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.019.

[29] Falkenhorst G, Remschmidt C, Harder T, Hummers-Pradier E, Wichmann O, Bogdan C. Effectiveness of the 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPV23) against Pneumococcal Disease in the Elderly: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOS ONE 2017;12:e0169368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169368.

[30] Berild JD, Winje BA, Vestrheim DF, Slotved H-C, Valentiner-Branth P, Roth A, et al. A Systematic Review of Studies Published between 2016 and 2019 on the Effectiveness and Efficacy of Pneumococcal Vaccination on Pneumonia and Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in an Elderly Population. Pathogens 2020;9:259. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040259.

[31] Breiman RF, Keller DW, Phelan MA, Sniadack DH, Stephens DS, Rimland D, et al. Evaluation of Effectiveness of the 23-Valent Pneumococcal Capsular Polysaccharide Vaccine for HIV-Infected Patients. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2633–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.160.17.2633.

[32] French N, Nakiyingi J, Carpenter LM, Lugada E, Watera C, Moi K, et al. 23–valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in HIV-1-infected Ugandan adults: double-blind, randomised and placebo controlled trial. The Lancet 2000;355:2106–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02377-1.

[33] Matanock A. Use of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine and 23-Valent Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years: Updated Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a5.

[34] Chien Y-W, Klugman KP, Morens DM. Bacterial pathogens and death during the 1918 influenza pandemic. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2582–3. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc0908216.

[35] Morris DE, Cleary DW, Clarke SC. Secondary Bacterial Infections Associated with Influenza Pandemics. Front Microbiol 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01041.

[36] Hughes JM, Wilson ME, Hughes JM, Wilson ME, Lee EH, Wu C, et al. Fatalities Associated with the 2009 H1N1 Influenza A Virus in New York City. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:1498–504. https://doi.org/10.1086/652446.

[37] Spooner LH, Scott JM, Heath EH. A BACTERIOLOGIC STUDY OF THE INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC AT CAMP DEVENS, MASS. J Am Med Assoc 1919;72:155–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1919.02610030001001.

[38] Buenen AG (Noud), Wever PC, Borst DP, Slieker KA. COVID-19 op de Spoedeisende Hulp in Bernhoven. NED TIJDSCHR GENEESKD 2020:6. https://www.ntvg.nl/artikelen/covid-19-op-de-spoedeisende-hulp-bernhoven.

[39] Murk J-L, van de Biggelaar R, Stohr J, Verweij J, Buiting A, Wittens S, et al. De eerste honderd opgenomen COVID-19-patiënten in het Elisabeth- Tweesteden Ziekenhuis. NED TIJDSCHR GENEESKD 2020:7.

[40] WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 is suspected n.d. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected (accessed April 13, 2020).

[41] Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, He J, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020;0:null. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

[42] Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 2020;395:1054–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

[43] CMMID. Response strategies for COVID-19 epidemics in African settings: a mathematical modelling study. CMMID Repos 2020. https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/covid-response-strategies-africa.html (accessed April 23, 2020).

[44] CMMID. Risks and benefits of sustaining routine childhood immunisation programmes in Africa during the Covid-19 pandemic. CMMID Repos 2020. https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/control-measures/EPI-suspension.html (accessed April 8, 2020).

[45] Vandenbroucke JP, Brickley EB, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CMJE, Pearce N. Analysis proposals for test-negative design and matched case-control studies during widespread testing of symptomatic persons for SARS-Cov-2 2020.

Appendix

Proportion of PPV23 serotypes among older adults:

The PSERENADE project aims to understand the impact of PCV10/13 on invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) incidence and serotype distribution using IPD data contributed by surveillance sites across the world. In settings with mature PCV10/13 infant immunization programmes, the estimated proportion of IPD in older adults (≥65 years of age) attributable to PPV23 serotypes is 67-79% for countries using PCV10 in infants and 68-71% for countries using PCV13. Excluding ST3 (PPV23-minus-ST3), these proportions drop to 48-66% and 51-57% respectively. Because effectiveness against ST3 has not been observed in all countries, the proportion of IPD in older adults attributable to PPV23-minus-ST3 is used here as a more conservative estimate of preventable disease. In the time period prior to PCV use in children, the estimated proportion of IPD in older adults attributable to PPV23-minus-ST3 serotypes was about 20% higher; this can be a proxy for countries without an infant PCV programme. However, most of the data included comes from high-income countries and may not be entirely representative of the serotype distribution in countries without a PCV programme, which are mostly low and middle income.

Risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection during a vaccination clinic visit:

Assume that contact reducing interventions spread the risk of COVID-19 out roughly equally over a 6 month period. This scenario is in line with model predictions for SARS-CoV-2 spread in the presence of a 50% reduction in contacts for the duration of 6 months. Assuming an R0 of 2.5 and a duration of infectiousness of 1 week means that about 60% of the population will have been infected at the end of the pandemic and that at any one time about 2% of the population is infectious. Further, assume that an adult attends a vaccination clinic and makes a total of 2-10 contacts (hereby 2 may reflect a scenario of effective measures to avoid contacts) related to that visit and that the probability of infection per potentially infectious contact is about 10% (R0 attributed over the number of contacts during the infectious period e.g. 2.5 transmissions during the two days before symptom onset and self-isolation, with 12 contacts per day before isolation). Then the probability for SARS-CoV-2 infection during that vaccine clinic visit is $P = 1 - (1 - 0.1)^{\text{#contacts}0.02} = 0.004\text{~}0.02$. Hence, the excess absolute risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection over the pandemic baseline risk is P(1-60%) and corresponds to a relative risk increase over the pandemic baseline risk of 0.3 to 1.4%.