LFD mass testing in English schools - additional evidence of high test specificity

This study has not yet been peer reviewed.

Background

Widespread testing for active SARS-CoV-2 infections with lateral flow devices (LFDs) was introduced to educational settings in England on 27 November 2020 for higher education, 4 January 2021 in all secondary schools and colleges, and 18 January 2021 in primary schools, school-based nurseries and maintained nursery schools. Since 5 November 2020, more than 4 million LFD tests have been administered in education settings. There are, however, concerns that large scale use of LFDs may lead to an overwhelming amount of false positive test results, with detrimental consequences due to loss of face-to-face teaching amongst isolating students, and loss of working time amongst working parents.

Methods

We used the weekly and nationally aggregated number of LFD tests (excluding unknown/void results) and positive LFD tests stratified by educational setting as reported by the NHS [1]. These tests were taken as part of the routine surveillance in educational settings among asymptomatic staff and pupils. From January 2021 schools were closed to all but the children of key workers while nurseries stayed open. In the majority of cases the tests were combined oral-nasal swabs not administered by trained healthcare staff, and the LFD test used was the Innova lateral flow antigen test. We calculated a lower bound for the specificity of the LFD when used in educational settings in England by assuming that, at worst, all positive tests might be false positive

Results

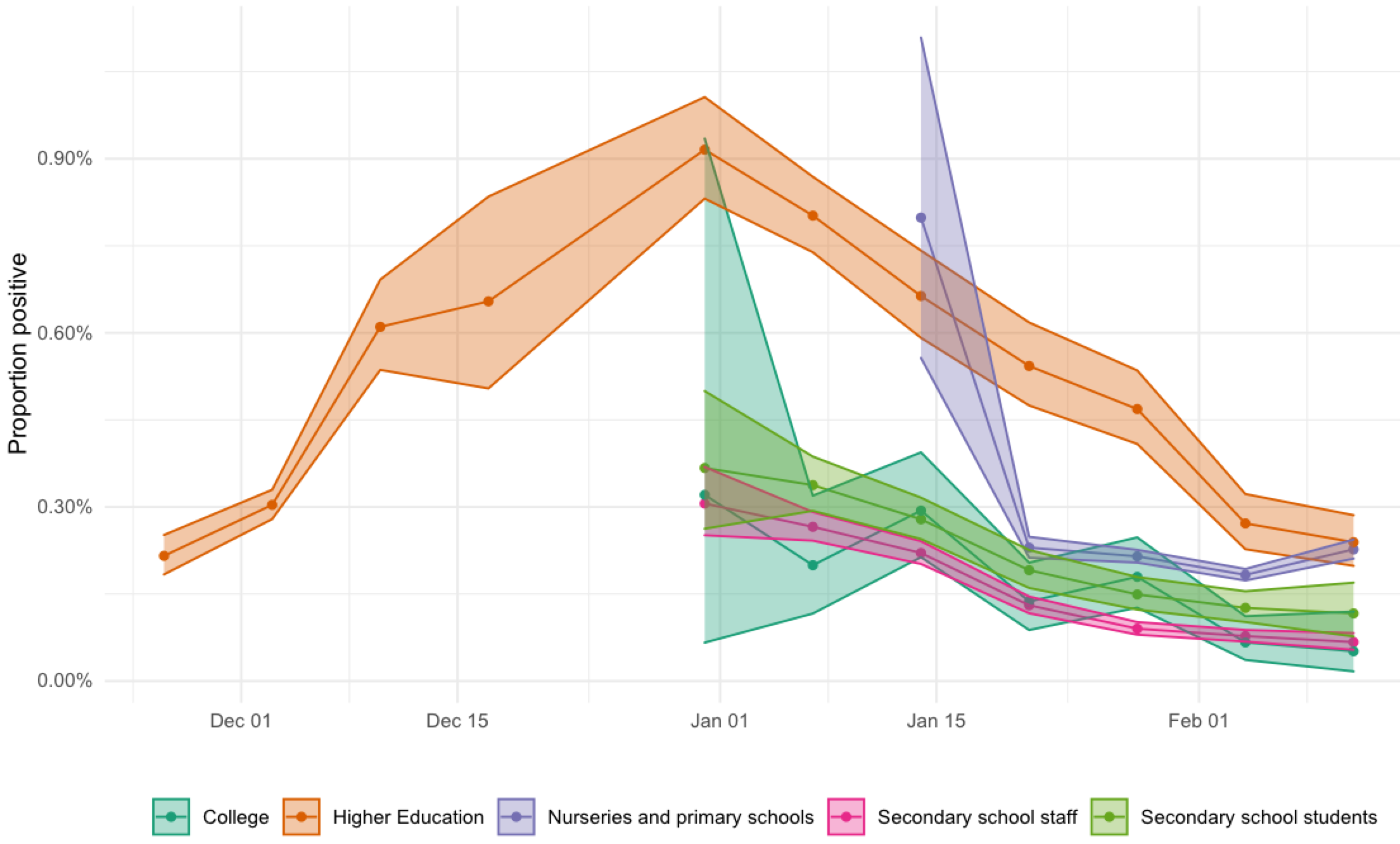

LFD test-positivity in educational settings followed the general epidemic, indicating that a substantial proportion of LFD positives were likely true positives. We estimate that with 95% probability the specificity of the LFD testing in educational settings was greater than 99.93% This is substantially higher than a previously reported estimate of 99.61% (99.40 - 99.76) when conducted by non-experts which, however, found that false positives test were showing weak indicator lines and were generally negative if re-testing with LFD. Our estimate implies that if the true prevalence is as low as 0.1% (0.5%) then more than 45% (80%) of test positives with LFD would be truly infected (assuming an LFD sensitivity of 80%, which is a conservative estimate for detecting infectiousness). Given this estimate we would expect a maximum 3254 (95% CI: 3367-3481) false positive tests among the over 4 million tests administered (including staff) until mid-February, implying detection of at least 7018 (6791-6905) true infections that could otherwise have gone undetected and transmitted further.

Conclusions

LFD tests have even higher specificity than previously reported and potentially even higher than the lower bound we could estimate here. Combined with their high sensitivity for detecting infectious infections LFD tests can therefore play an important part of pandemic mitigation strategies in educational settings and elsewhere. Nevertheless, as SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence declines the proportion of true positives among the test positives will similarly decrease and so will the utility of mass testing compared to its societal and monetary cost. Disaggregated data by school could further improve the precision of our estimates and help better evaluate the expected number of false positives.

Figure: LFD test positivity as proportion of all LFD tests conducted in different settings (mean: points and lines, 95% exact binomial confidence intervals: shaded area).