Effective transmission across the globe: the role of climate in COVID-19 mitigation strategies

This study has not yet been peer reviewed.

COVID-19 has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO), owing to its rapid global spread and alarming ability to quickly overwhelm healthcare services with patients requiring critical care [1]. A pertinent question for COVID-19 mitigation strategies is whether the SARS-CoV-2 virus is less transmissible in hot and humid climates. Some studies support that notion. Sajadi et al.found that regions with established community outbreaks had a lower average temperature and specific humidity compared to areas that did not report significant community transmission [2] and similar findings have been observed using ecological niche modelling [3]. Similarly, Wang et al. reported a decrease in transmission intensity associated with an increase in temperature and relative humidity [4]. An environmental study of SARS-CoV-1 reported reduced survival of the virus at higher temperatures and humidity [5] . Such studies have been interpreted by some as sufficient evidence to assume that rising temperatures in boreal summer will likely facilitate COVID-19 control. However, these findings are prone to confounding, including the delay in spread to warmer regions of the world due to travel patterns [6] . Hence, it is essential to contextualize these with the current global spread of COVID-19.

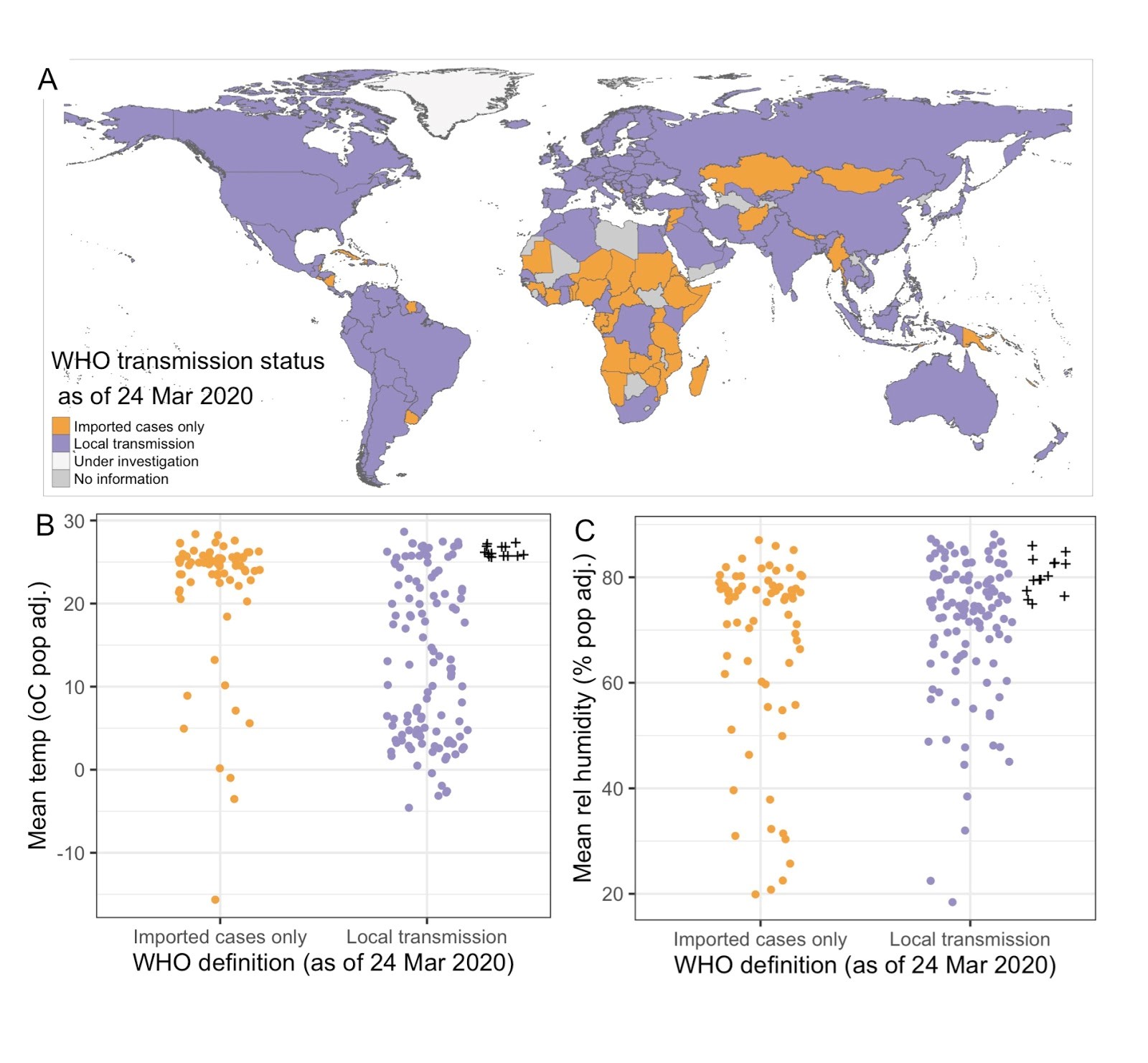

As of 24 March 2020, 117 countries and territories across the globe have reported local SARS-CoV-2 transmission, 71 have reported imported cases only, six are under investigation and the remainder has not yet reported any cases (Figure 1A) [7]. All WHO regions have at least six countries with confirmed local transmission, effectively spanning all climatic zones, from cold and dry to hot and humid regions. Notably, countries reporting local transmission include Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand, with much movement between them and China. However other countries outside of Asia including Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Panama and Paraguay, with mean ambient temperatures between 1 January 2020 - 14 March 2020 greater than 25°C (Figure 1B) also report local transmission.

The ability of SARS-CoV-2 to effectively spread globally, including in warm and humid climates, suggests that seasonality cannot be considered a key modulating factor of SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility. While warmer weather may slightly reduce transmission of SARS-CoV-2, there is no evidence to suggest that warmer conditions in northern hemisphere summer months will reduce the effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 transmission to an extent that few additional interventions are needed to curb its spread. Further studies on the impact of climate variability, air pollution and other extrinsic factors on COVID-19 transmission will need to consider connectivity from locations with a high incidence, population susceptibility and surveillance for respiratory infections. For the time being, policy makers must focus on contact reducing interventions and any COVID-19 risk predictions based on climate information alone should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 1. (A) Global map of WHO transmission status (as of 24 March 2020) for COVID-19 and comparison of WHO transmission status with average population adjusted (B) temperature and (C) relative humidity between January 2020 - 14 March 2020. ERA5 hourly 2-metre temperature and dewpoint temperature data was extracted from the Copernicus Climate Change Service Data Store [8]. Relative humidity was calculated using the August–Roche–Magnus formula [9] . Seasonal averages for each country are population adjusted. Countries with local transmission with an average temperature above 25°C and relative humidity above 70% are indicated (+), and are Brunei Darussalam, Fiji, French Guiana, French Polynesia, Guam, Guyana, Indonesia, Liberia, Malaysia, Maldives, Panama, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka.

References

1 WHO. WHO characterizes COVID-19 as a pandemic (11 March 2020) https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen

2 Sajadi MM, Habibzadeh P, Vintzileos A, Shokouhi S, Miralles-Wilhelm F and Amoroso A. Temperature, Humidity and Latitude Analysis to Predict Potential Spread and Seasonality for COVID-19 (March 5, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3550308 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3550308

3 Wang J, Tang K, Feng K and Lv W. High Temperature and High Humidity Reduce the Transmission of COVID-19 (March 9, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3551767 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3551767

4 Araujo MB and Naimi B. Spread of SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus likely to be constrained by climate (March 16, 2020) Available at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.12.20034728

5 Lai S, Bogoch I, Ruktanonchai N, Watts A, Lu X, Yang W, Yu H, Khan K and Tatem AJ. Assessing spread risk of Wuhan novel coronavirus within and beyond China, January-April 2020: a travel network-based modelling study (March 9, 2020). Available at medRxiv 2020.02.04.20020479 or https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.04.20020479

6 Chan KH, Peiris JS, Lam SY, Poon LL, Yuen KY, Seto WH. The Effects of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Viability of the SARS Coronavirus. Adv Virol. 2011; 2011: 734690. doi:10.1155/2011/734690

7 WHO. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports accessed 26 March 2020.

8 Copernicus Climate Change Service4 on the 22 Mar 2020 (C3S): ERA5: Fifth generation of ECMWF atmospheric reanalyses of the global climate. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store (CDS), 2017; accessed 22 Mar 2020. https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#

9 Alduchov OA and Eskridge RE. Improved Magnus’ form approximation of saturation vapor pressure. J. Appl. Meteor., 1996; 35; 601–609.