Forecasting critical care bed requirements for COVID-19 patients in England

This study has not yet been peer reviewed.

Aim

To estimate critical care bed demand for COVID-19 cases in England for the next two weeks.

Summary

The COVID-19 epidemic in the UK has reached the point of widespread, sustained transmission. Because of the rapidly increasing number of patients, the availability of critical care beds to treat them and limit avoidable mortality is an urgent concern. Bed demand in intensive care and high dependency units (ICU/HDU) will depend on two essential factors: the number of admissions of COVID-19 patients to ICU/HDU, and the duration of their hospitalisation.

To anticipate the increasing demand for ICU/HDU beds, we first quantified the epidemic growth using the First Few Hundreds (FF100) linelist data collected by Public Health England. We only considered ‘sporadic’ cases identified through sentinel or hospital-based surveillance, i.e. excluding imported and secondary cases because these largely reflect entry screening and contact tracing policies rather than the actual growth of the epidemic locally. Reporting delays were estimated using maximum-likelihood (ML) fitting of a discretised Gamma distribution (mean: 7.6 days, coefficient of variation: 0.5), and used to define the ‘trusted’ time period, in which we expect at least 95% of symptom onsets to have been reported. A daily growth rate of 0.1(CI95%: 0.02 ; 0.18) corresponding to a doubling time of 7 days (CI95%: 3.8 ; 41.4) was estimated by ML fitting of a log-linear model to daily incidence of symptom onset within the trusted period. Note that this growth rate is generally lower than other estimates1, which may reflect underreporting in an ICU surveillance system still being scaled up, or impact of early interventions. As a result, we may under-estimate future admissions and bed requirements.

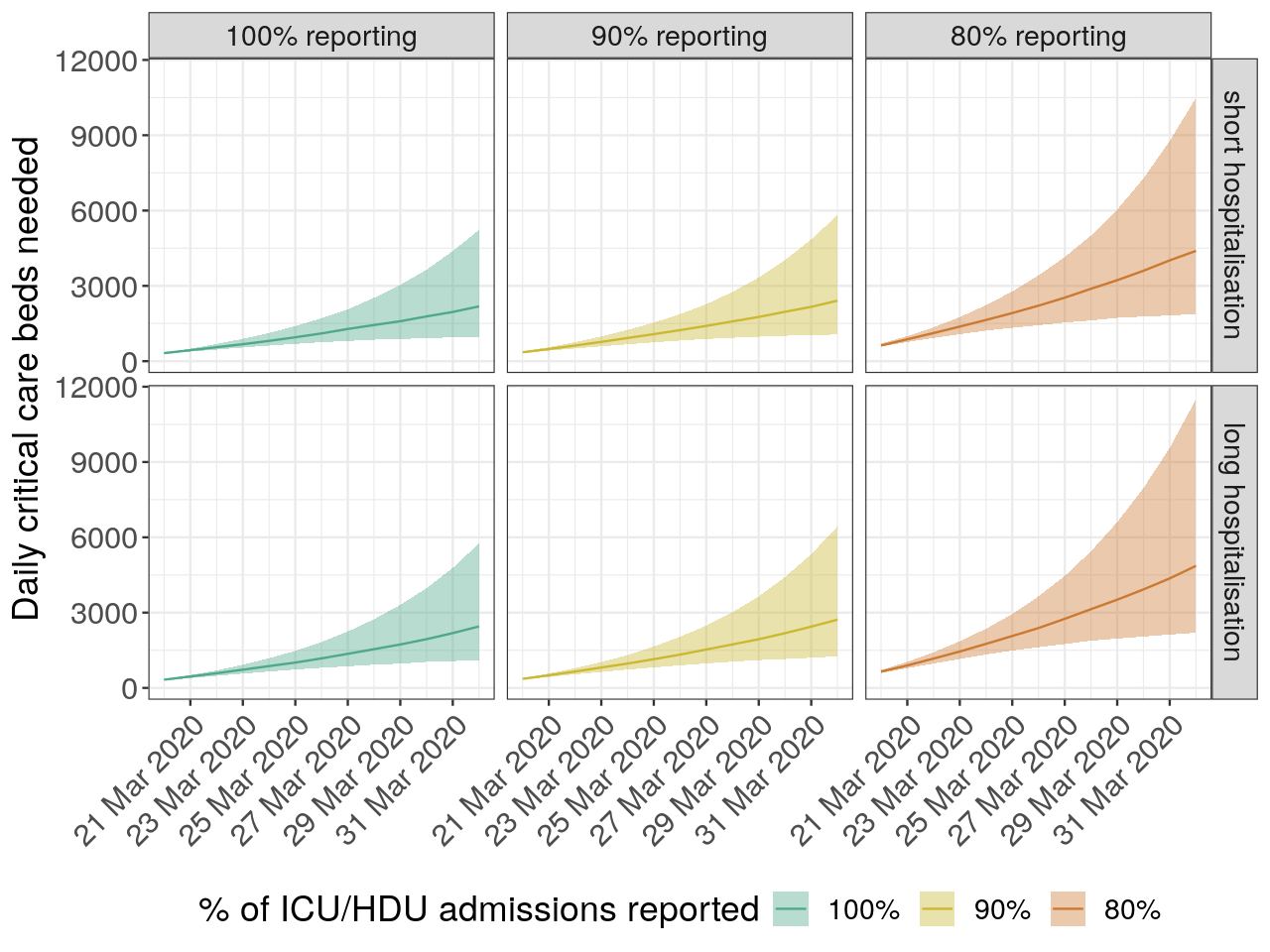

Figure 1: Predictions of critical care bed needs. This figure shows the numbers of new patients requiring beds in critical care for COVID-19 projected from current admissions data in ICU/HDU in England. Mean needs and their 95% confidence intervals are indicated by the plain lines and ribbons, respectively. Columns and colors present results for different assumed reporting of admissions, from full reporting (100%, left), 90% (middle), and 80% (right) reporting. Rows indicate results for different assumed distributions of the duration of hospitalisation: ‘short’ (median: 8 days2) and ‘long’ (median: 10 days3).

Assuming the proportion of COVID-19 cases needing critical care remains constant over time, we applied this growth rate to current admission data to forecast ICU/HDU admissions for the next two weeks, using admissions reported up to the 18th March 2020 as a starting point. We took into account potential underreporting of case admissions by considering three scenarios assuming 100%, 90% and 80% of admissions were reported. For each admission thus predicted, we simulated durations of hospitalisation using two recently estimated distributions with median length of stay of 8 days2 (discretised Weibull: shape = 2, scale = 10) and 10 days3 (discretised Weibull: shape = 2.2, scale = 12). This allowed us to forecast daily critical care bed needs (Figure 1). Despite substantial uncertainty, all scenarios forecast a marked increase in bed needs in ICU/HDU, with average demand ranging from 1,931 (CI95%: 921 ; 4,361) to 4,364 (CI95%: 2,099 ; 9,568) critical care beds every day by the end of March 2020 (Table 1). These results imply that unless transmissibility is strongly reduced in the coming days, ICU/HDU capacity for COVID-19 in England (in January 2020: 4,123 critical beds for adults, 312 in paediatrics4) may be challenged by the end of March, without even considering capacity requirements for other conditions. These concerns add to increased risks of nosocomial transmission, which may put additional pressure on bed capacity as the epidemic grows.

Table 1: Predictions of critical care bed needs. This table provides predicted demand for critical care bed for COVID-19 patients needing ICU/HDU admission on the 31st March 2020 in England. Numbers indicate the mean number of beds needed, with associated 95% confidence intervals representing uncertainty in both reporting delays and projected cases needing admission. Shorter and longer duration of hospitalisation correspond to two different assumed distributions with medians of 82 and 10 days3. ‘Reporting’ refers to the assumed percentage of COVID-19 cases admitted in ICU/HDU reported in current databases.

| 100% Reporting | 90% Reporting | 80% Reporting | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter duration of hospitalisation | 1,931 (921 ; 4,361) | 2,194 (1,007 ; 4,864) | 3,936 (1,869 ; 8,791) |

| Longer duration of hospitalisation | 2,171 (1,104 ; 4,772) | 2,426 (1,192 ; 5,342) | 4,364 (2,099 ; 9,568) |

Regional Results

The previous analyses are repeated for London, and other NHS regions separately.

London

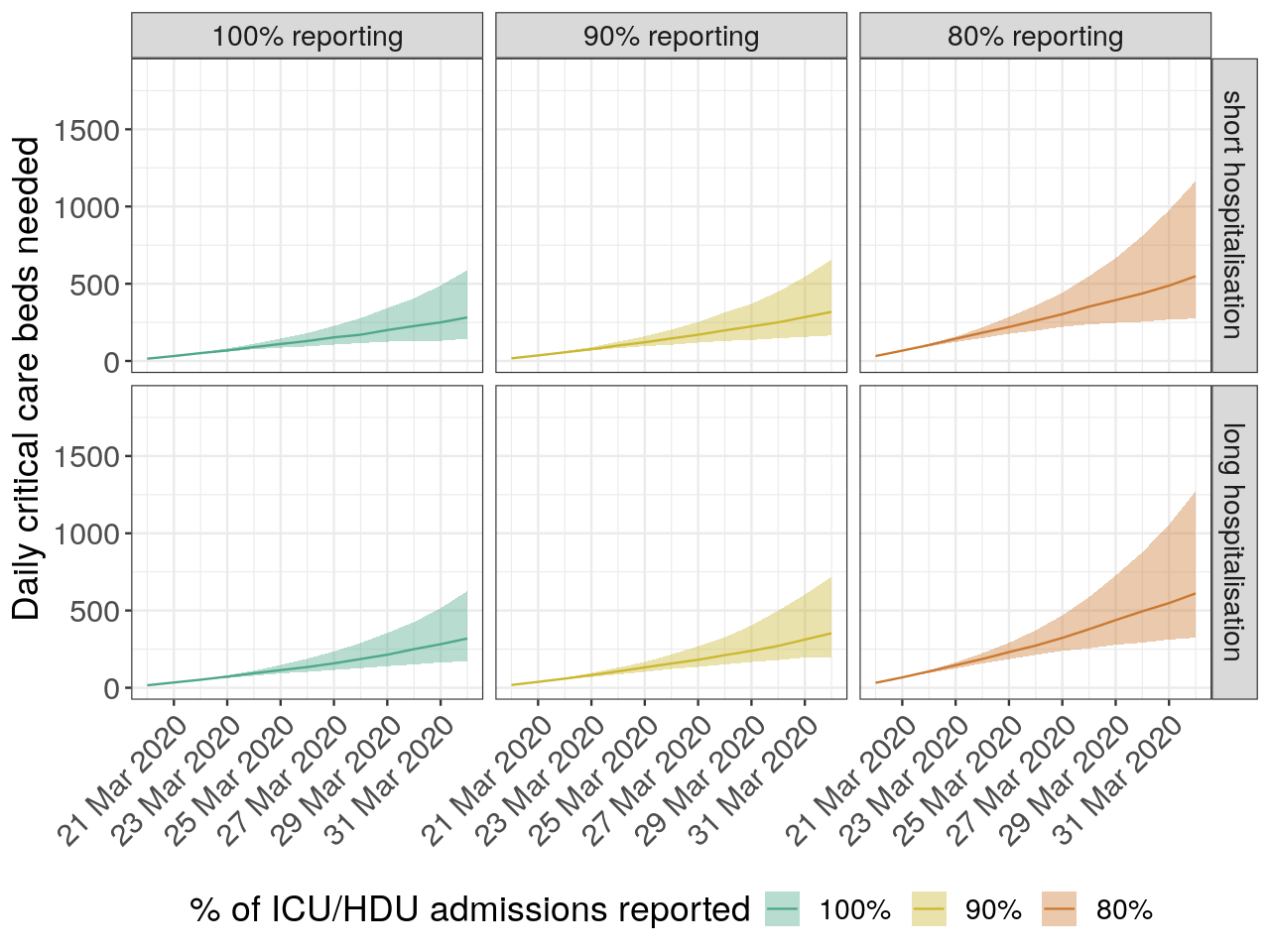

For the analysis of London specifically, the starting point for admissions projections is taken from the 20th March 2020. Average predicted demand ranges from 198 (CI95%: 130 ; 315) to 548 (CI95%: 312 ; 1,056) critical care beds every day on the 31st March 2020.

Figure 2: Predictions of critical care bed needs - London only This figure shows the numbers of new patients requiring beds in critical care for COVID-19 projected from current admissions data in ICU/HDU in England. Mean needs and their 95% confidence intervals are indicated by the plain lines and ribbons, respectively. Columns and colors present results for different assumed reporting of admissions, from full reporting (100%, left), 90% (middle), and 80% (right) reporting. Rows indicate results for different assumed distributions of the duration of hospitalisation: ‘short’ (median: 8 days2) and ‘long’ (median: 10 days3).

NHS regions (excl. London)

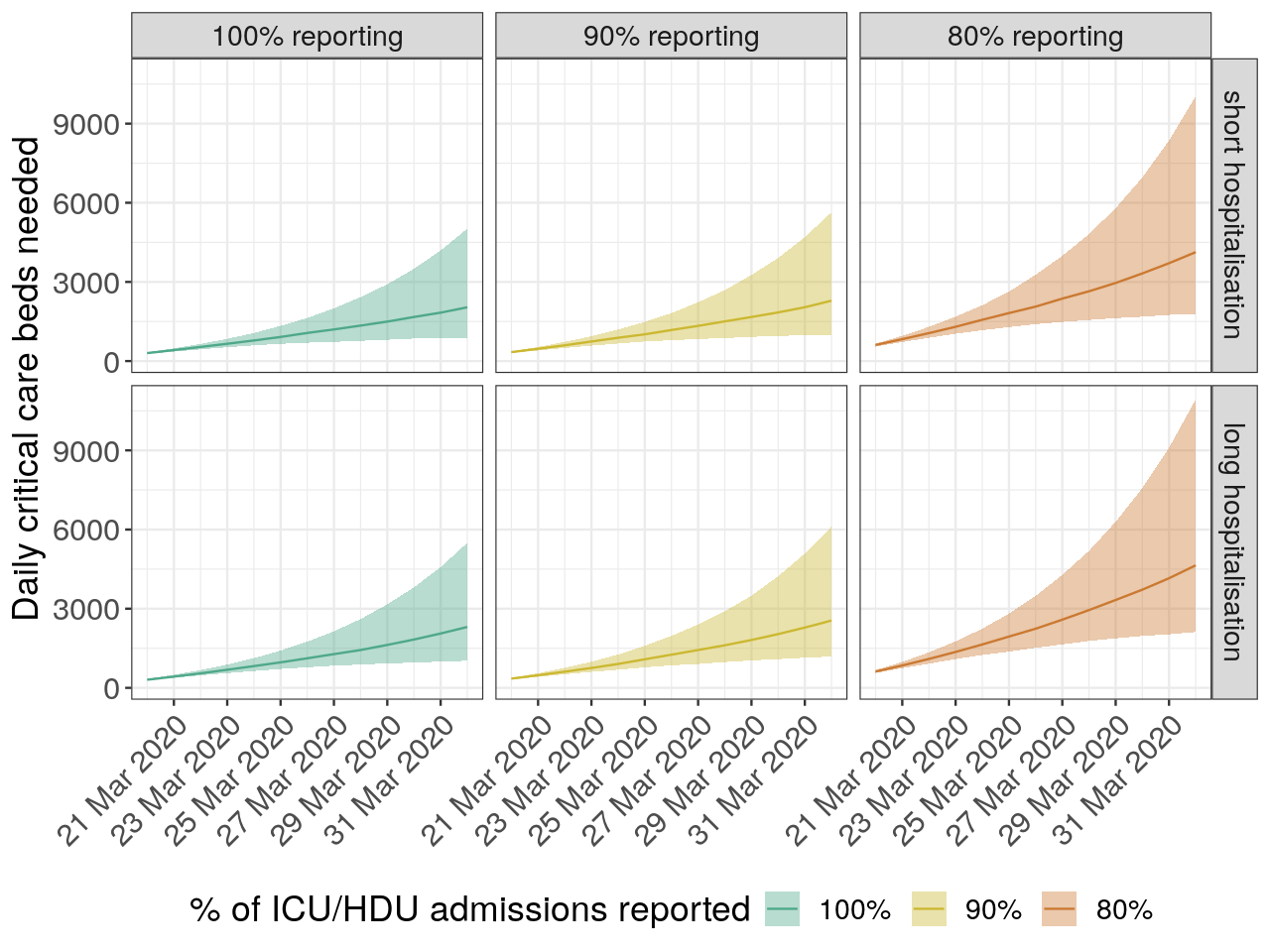

For the analysis excluding London, the starting point for admissions projections is taken from the 18th March 2020. Average predicted demand ranges from 1,835 (CI95%: 862 ; 4,193) to 4,155 (CI95%: 2,028 ; 9,099 ) critical care beds every day on the 31st March 2020.

Figure 3: Predictions of critical care bed needs - NHS regions excluding London. This figure shows the numbers of new patients requiring beds in critical care for COVID-19 projected from current admissions data in ICU/HDU in England. Mean needs and their 95% confidence intervals are indicated by the plain lines and ribbons, respectively. Columns and colors present results for different assumed reporting of admissions, from full reporting (100%, left), 90% (middle), and 80% (right) reporting. Rows indicate results for different assumed distributions of the duration of hospitalisation: ‘short’ (median: 8 days2) and ‘long’ (median: 10 days3).

App

Since the initial post, the model has been generalised to any type of hospitalisation and implmented in a web-app.

References

- Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: Early Experience and Forecast During an Emergency Response. JAMA 2020; published online March 13. DOI:10.1001/jama.2020.4031.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; published online March 11. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

- Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A Trial of Lopinavir-Ritonavir in Adults Hospitalized with Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020; published online March 18. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2001282.

- NHS. Critical Care Bed Capacity and Urgent Operations. NHS Statistics. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/critical-care-capacity/critical-care-bed-capacity-and-urgent-operations-cancelled-2019-20-data/ (accessed March 21, 2020).

Acknowledgements

The named authors (TJ, ESN, MJ, OLPDW, GK, RME, AJK, CABP, WJE) had the following sources of funding: TJ receives funding from the Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) project ‘RECAP’ managed through RCUK and ESRC (ES/P010873/1), the UK Public Health Rapid Support Team funded by the United Kingdom Department of Health and Social Care and from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) - Health Protection Research Unit for Modelling Methodology. ESN receives funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number: OPP1183986). MJ receives funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation (grant number: INV-003174) and the NIHR (grant numbers: 16/137/109 and HPRU-2012-10096). SRP receives funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant number: OPP1180644). RME receives funding from HDR UK (grant number: MR/S003975/1). SF is supported by a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant number 208812/Z/17/Z). AJK receives funding from the Wellcome Trust (grant number: 206250/Z/17/Z). GMK was supported by a fellowship from the UK Medical Research Council (MR/P014658/1).

The UK Public Health Rapid Support Team is funded by UK aid from the Department of Health and Social Care and is jointly run by Public Health England and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The University of Oxford and King’s College London are academic partners. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Authors’ contributions

In alphabetic order: JE, MJ, TJ developed the methodology. ESN, MJ, TJ contributed code. TJ performed the analyses. ESN, TJ reviewed code. ESN, TJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. AK, CP, ESN, JE, MJ, OlP, GMK, RE, SF, TJ contributed to the manuscript.

CMMID COVID-19 Working Group gave input on the method, contributed data and provided elements of discussion. The following authors were part of the Centre for Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Disease 2019-nCoV working group: Billy J Quilty, Christopher I Jarvis, Petra Klepac, Charlie Diamond, Joel Hellewell, Timothy W Russell, Alicia Rosello, Yang Liu, James D Munday, Sam Abbott, Kevin van Zandvoort, Graham Medley, Samuel Clifford, Kiesha Prem, Nicholas Davies, Fiona Sun, Hamish Gibbs, Amy Gimma, Nikos I Bosse, Sebastian Funk. Each contributed in processing, cleaning and interpretation of data, interpreted findings, contributed to the manuscript, and approved the work for publication.